QUICK LINKS

ARTICLE

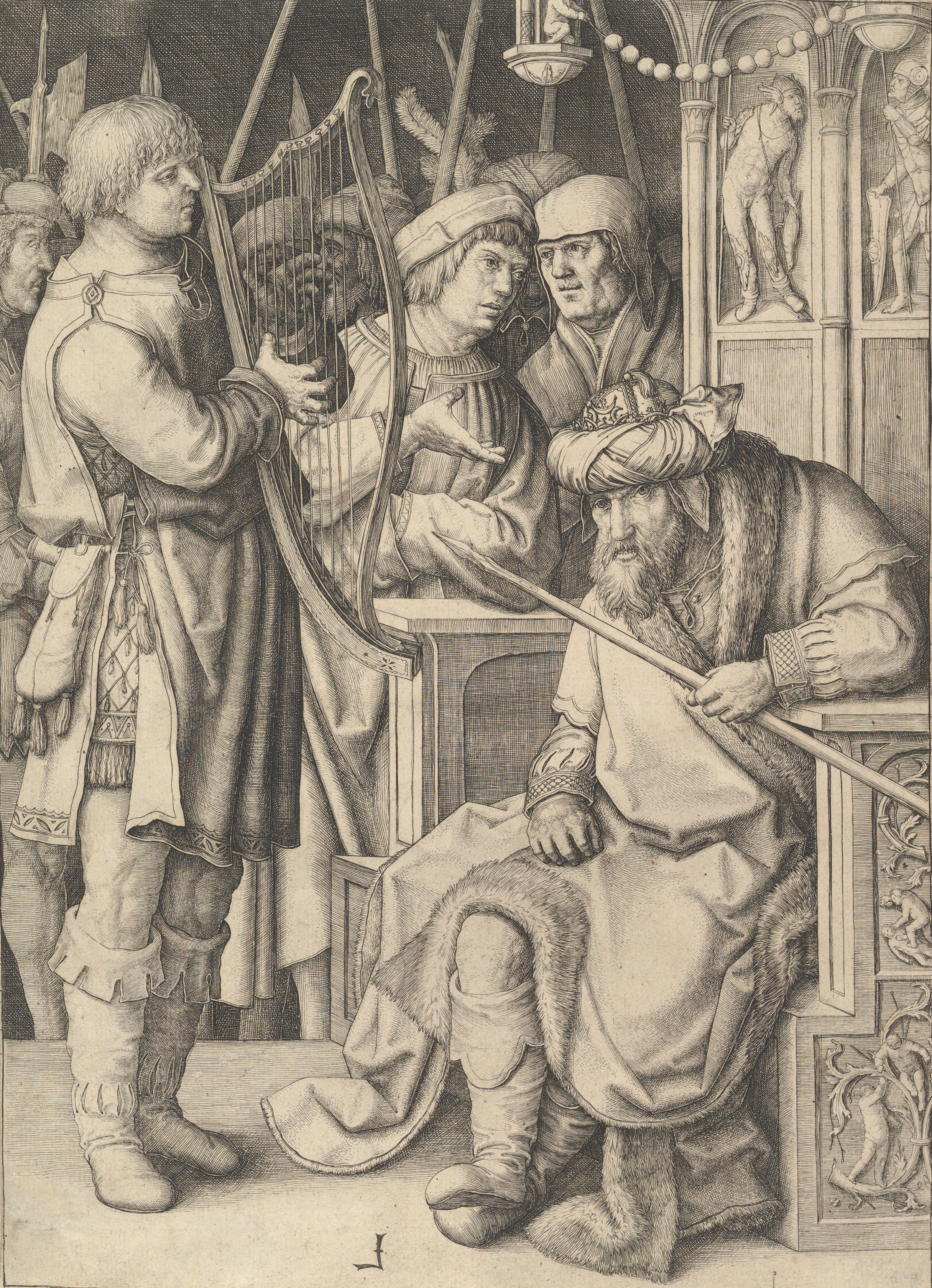

DAVID’S HARP, SAUL’S SPEAR:

THE ABUSE OF CHURCH MUSICIANS

Dedicated to all those who have

lighted my path and lifted me up.

You know who you are, and I love you.

“The next day, an evil spirit came forcefully on Saul. He was prophesying in his house, while David was playing the lyre, as he usually did. Saul had a spear in his hand and he hurled it, saying to himself, ‘I’ll pin David to the wall.’ But David eluded him twice.”

[1 Samuel 18: 10–11]

_________________________

David Playing the Harp Before Saul

Lucas van Leyden (Netherlands), c. 1508

Engraving, The Art Institute of Chicago

INTRODUCTION

The pastor was meeting with an associate in the office. Disagreements ensued, and the pastor became furious, suddenly picking up a piece of furniture and throwing it at them.*

Between services on Christmas Eve, an organist ducked into their music room, where all at once they found themselves pinned against the wall by the enraged spouse of a choir member.

While in the hospital recovering from surgery, a music director discovered they had been fired by reading the church newsletter.

A young church musician, proud to be networking with older, esteemed colleagues, accepted an invitation for drinks. The next thing they remembered was waking the following morning, having been drugged and sexually assaulted.

*They/them is used for third person singular for reasons of anonymity.

In September 2022 I created an anonymous survey for church musicians who had left the field. The response was immediate and disturbing, with many stories of abuse and wounding. A few months later I generated a second survey focusing on abuse within the field, which results were more alarming. Although reports of verbal abuse were most common, stories of physical and sexual abuse were not rare. There were numerous reports of teachers having sex with their students, clergy physically and verbally abusing staff members, and church leaders acting deceitfully towards their employees.

I was overwhelmed by the total number (440) of respondents and the darkness of their experiences, and made it my mantra that God is Good, even when the Church is not. One respondent kindly wrote, “I’m sure your heart is broken hearing the stories, so take care of yourself in the process.”

A colleague frequently quips that no one ever looks back at church history and says, “Aha! Music was the problem!” And yet church musicians continue to face all kinds of difficulties and wounding. I hold these stories in my heart, and lift them up to the Light with prayers for reform and healing in the Church, and in our profession.

SET APART FOR SERVICE

In the ancient Hebrew scriptures, we read that of the 38,000 Levites whom King David appointed to the Lord’s service, 4000 were musicians. They lived in the chambers of the temple, engaged in their work day and night. [1] Some centuries later, we find Nehemiah rebuking the people of Jerusalem for not giving tithes and offerings, which forced priests and musicians to work in the fields. [2]

Pastor James R. Doggette, Sr. remarks about these passages, “There’s something spiritual [sic] about dogging our own people... We pay a plumber top price to fix our toilets, but want to argue about giving a preacher or musician some money... What’s happening when we require a musician to work at Walmart eight hours a day, and then at the end of the day set their family aside and spend their spare time working with a choir and planning the church music program?” Doggette explains that God directed so much money to be spent on the Sanctuary service that we can't even calculate its worth. [3] “But we want to run church operations with people who do church as a hobby. It's not biblical.” [4]

Clearly, things were complicated with David & Saul. So too it is with modern church music, which may be the most professionally diverse field, encompassing amateurs, conservatory and/or seminary trained musicians, volunteers, part- and full-time employees. According to the Bureau of Labor and Statistics, U. S. churches employ around 11,000 musicians, [5] while the American Guild of Organists lists membership at 14,700. [6] Meanwhile the Hartford Institute estimates the number of U. S. churches at around 350,000, [7] leaving us to guess at the real numbers. To further complicate matters, we work for people who receive minimal musical training: who rarely comprehend what it takes to do our jobs well. Even so, should it be difficult to be kind and fair to one another, especially in the context of serving God? Put down your spear, Saul. We’re just trying to make some beautiful music.

HOW ABUSE HAPPENS

Psychologists tell us most abusers were abused themselves, but don’t perceive themselves as abusive. Such a person tends to hide things both from themselves and others. Leaders who are not careful with power can become corrupt, particularly if they are insecure. It is important for such people to read stories of abuse with an open and honest heart, willing to recognize ways in which they may have behaved hurtfully. Dr. Paul Westermeyer of Luther Seminary has written that systemic abuse is more characteristic of clergy, but both musicians and clergy are capable of horrible things. [8] Of course this is also true of teachers and colleagues.

The Rev. Dr. Victoria Sirota alerted me to Harvard professor Rev. Peter Gomes (author of The Good Book: Reading the Bible with Mind and Heart) having said the following about Evil. First, it’s real. Second, good people are not as smart as they think. Third, good people need all the help they can get. “Good people do bad things because good people aren’t good enough,” wrote Gomes. [9]

Oxford University research psychologist Kevin Dutton reports in The Wisdom of Psychopaths that clergy are No. 8 on the list of likely professions for psychopaths in the UK. (Interestingly, creative artists are No. 8 on the least likely list.) [10] Dutton explained in an interview that the Church has a hierarchy very much to do with the implementation of power. “I’ll always remember a high-powered Church person saying, ‘Kev, I don’t believe in God. I’m just good at Him.’ And, you know, I’ve met a lot of psychopaths in a lot of different circumstances, but even now that was probably one of the most chilling things anyone had actually said to me.” [11]

In Broken Hearts, Shattered Trust: Workplace Abuse of Staff in the Church, the Rev. Dr. John K. Setser observes that pastor abuse is not about being demanding or having a bad day, but rather the use of power to control, manipulate, demean, or exploit staff — whether over time or in one catastrophic event. He describes such abuse as a trust injury: a wounding by someone trusted to represent love, and to provide care, guidance, and protection. [12] Abused staff often feel shocked, traumatized, mystified that such treatment could occur in a church, abandoned by their church family, and left alone to speculate about what went wrong and whom they can trust. Post-traumatic stress or dissociative identity disorders have been reported, along with feeling spiritually broken to the point of leaving their profession or the Church altogether.

A colleague recently told me their clergy friends are seeming more wounded now than in the past, and that seminaries are often missing the human/pastoral component. Newly ordained pastors are often thrown into their posts untrained to deal with people or to manage a staff. Even many second-career clergy struggle to grasp how to run a church well.

Setser points out that pastors often feel they are being evaluated according to measurable results such as money, numbers, programs, and facilities. If congregational expectations aren’t met, the pastor can blame themselves, adding to the stress. Thus many clergy come to adopt a corporate model in which people can be sacrificed, and “looking successful replaces love as the key ingredient.” [13]

Of course clergy are not the only abusers. Lay leaders can wield the power to disrupt a person’s career and upend their family’s lives. Abuse by teachers and mentors wreak havoc on their student’s mental health as well as their dreams. Staff can act horridly to colleagues and guests alike. I remember bringing a babysitter, a recent Christian convert, on various recital trips. At one location she was distressed by the behavior of both clergy and staff, asking me, “Is this really a church?”

TYPES OF ABUSE

Workplace abuse is illegal as well as unethical. Business writer Valerie Bolden-Barrett describes the four main types as follows: Violence is defined by OHSA as an act or threat of physical harm, including intimidating verbal abuse. Risks are highest for those who work alone, at night, or in isolated areas. Bullying includes isolating and threatening or demeaning words. Discrimination exists when hiring, firing, pay, disability, training, opportunities, and other decisions adversely affect particular groups of people. Harassment consists of actions or comments that are offensive or create a hostile workplace, and applies to workers who are witnesses as well as those harassed.

Possible effects of workplace abuse according to Bolden-Barrett are emotional (depression, fear, a loss of self-confidence, anxiety, feelings of helplessness, PTSD,) physical (high blood pressure, headaches, ulcers, weight loss, sleeplessness,) and social (productivity, poor performance, withdrawal from fellow workers, violence.) [14] Of course, as many mental health professionals maintain, sometimes it is the less horrifying stories which do the most damage.

INSTITUTIONAL CHAOS

The inability to respect peoples’s rights and boundaries is systemic in many institutions, not the least of which is the Church. While copious publications exist for clergy hiring, compensation, and benefits in most denominations, similar guidelines rarely exist for staff. One organization inexplicably specifies only administrators, bookkeepers, and sextons in its list of lay employees. [15] Another differentiates compensation policies between musicians and other staff, mandating the top salary for an administrator (no experience specified) to be more than for a musician with a doctorate and 25 years in the field.

Some of these problems stem from grave misunderstandings about musicians and their calling, training, and dedication to the Church. It is difficult to stomach some of the descriptions clergy make of their musicians, such as found in Eileen Guenther’s Rivals or a Team? Clergy-Musician Relationships. Criticisms that musicians think of themselves as performers (rather than concerned with performing the liturgy well), or having too much power (rather than real power, which is always held by the leaders) are discouraging. Often clergy become annoyed with musicians’ reasonable stated boundaries, such as hours per week, compensation, and necessary advance planning and preparation. Other times they make harmful and ridiculous restrictions, such as the pastor who informed their new organist they could not practice on Fridays or Saturdays.

Though antidiscrimination laws cover all areas of employment from hiring to firing, and both OSHA and the EEOC recommend zero-tolerance policies for workplace abuse, church staff are often not protected by these laws because of the small number of employees. Reports of abuse in academic settings are generally met with swift and serious investigation, but that is only if the victim feels courageous enough to speak up.

SECRETS AND DENIAL

Denial is a key factor enabling abuse. In an article about the 2019 survey of the U. S. Roman Catholic workforce in America, diocesan priests were reported as least likely (20%) to regard sexual misconduct as a continuing issue, compared with 40% of lay employees and 56% of nuns. [16] In the same article, Catholic League president Bill Donohue is quoted as saying that many falsely conflate old headlines with modern behavior: “Most of the bad guys, most of the priests who molested, are either dead or they’re out of ministry. That’s not an opinion, that’s a fact.” [17]

Thomas G. Plante, a frequent apologist for the Catholic church, says there is no evidence that priests sexually abuse children/teens at higher rates than other groups of men. [18] Apart from questioning this statement, one simply has to wonder whether we’re okay with not holding ordained persons to a higher standard. The issue is not that it happens at some rate relative to other men, it is that it happens at ALL in an institution founded on “loving your neighbor as yourself” — and that there is usually no kind of satisfactory recourse or resolution for the victim.

Twelve-steps groups teach that our secrets make us sick, perpetuating dysfunctional families and relationships. Edwin H. Friedman, family therapist, rabbi, and author of the acclaimed Generation to Generation: Family Process in Church and Synagogue explains that secrets exacerbate pathologies unrelated to the secret, causing high levels of anxiety. “The formation of a family secret is always symptomatic of other things going on.” [19] Anxieties only decrease when secrets are revealed, and when the family works at the surfacing issues that precipitated the secret.

After the elephant in the room is addressed, and realities brought to the forefront, then change, reform, and healing can begin. One respondent wrote, “Your taking on this project I hope will help bring to light this sort of behavior in the world of the professional organist, and let victims know they are not alone and that they are affirmed in how they feel after such assaults.”

METHODS

The two anonymous surveys were created on JotForm, and disseminated on more than twenty Facebook pages for church musicians or organists. 152 persons responded to the first survey (most between September and November 2022), and 288 to the second (January 2023) for a total of 440 individual responses. Many respondents provided an email address for an interview or follow-up questions, which was helpful in ascertaining the severity of the abuses.

Written-in responses (“other”) that matched defined categories were moved accordingly. Stories were edited for clarity, relevance, and brevity, and in some cases to modify a distinctive, recognizable voice. I used “they/them” for the third person singular for reasons of anonymity, and changed certain identifiable details.

Several responses were from luminaries in our field; clearly our best and brightest have not been spared from this disease. In a few instances I included a second-hand story, but only after ascertaining the trustworthiness of both respondent and victim. As the process was self-selecting, it was not surprising that most respondents had at least one story to tell about themselves. Numerous people seemed triggered and angry telling their stories, with some hopeless about the possibility of change.

Many of these stories seem unbelievable, but through my own journey of recovery from some frankly unthinkable things, I have learned that people generally do not make these incidents up — especially when no abuser is named, as was the case with all but two responses. Even if many are exaggerating, it is distressing to see so many people passionately enter music ministry, to come out spiritually bereft, depressed, anxious, angry, and/or physically wounded. I did not categorize different kinds of abuses in the survey questions, although the respondents specified them in their stories.

Survey questions and complete data are found at the links (both above and below), and a bibliography follows the notes at the close of the article. Of particular interest at the end of Survey Two Stories are the flood of responses concerning what exactly needs to change, and what might be helpful to effect that change — this section may prove to be the most valuable result of the project.

PUSHBACK

It was eye-opening to receive pushback on this project. I was reprimanded for implying that all church musicians are innocent. One Facebook group deleted my survey link, and both removed and blocked me from the group. A dear friend implored me not to write anything negative about the Church. Someone with a master’s in psychology said it sounded like a “Me-Too for organists,” leaving me to wonder how seriously they take their clients. Several demanded what I thought could come out of this. Some complained of organists “abusing” churches by taking positions because they want free access to a good organ. The head of a professional organization asked me to remove my post until I had met with them to discuss my research. Clergy wrote to inform me that the musicians they had fired were at fault. One respondent actually declared my intentions were evil, and complained that the “Woke Movement” is hijacking the true gospel and devaluing classical music. Wow.

Perhaps most telling was a collective hesitancy in speaking up: a conscious or unconscious unwillingness to talk. Many agreed to be interviewed, but wouldn’t set a time. Several didn’t pick up the phone, later offering excuses. One kept saying, “I’ll do the interview but not now.” Others said it was too traumatic to speak aloud, or even write out the details. There was a scarcity of public comments or “likes” on the postings with the survey links, which runs counter to my experience on social media. There is a lot of fear here.

There was however considerable support, and indeed prayers. I never considered halting the project when so many people were saying, “Thank you.” “Thank you for doing this.” “Thank you for shining a light on this issue.”

SURVEY ONE

Of the 152 respondents to the survey “Church Musicians Not Presently Employed in Church Music,” 95% had earned a college degree in church music or organ, and 71% had at least one graduate degree in the field. 30% had worked at least once in a full-time position, 57% in a 20–30 hour position, 86% in a 10-19 hour position, and 33% in a position of less than 10 hours per week.

Respondents indicated one or more of the following reasons for leaving church music:

60% said “Lack of respect or poor treatment by clergy, staff, or congregation”

59% said “Inadequate Salary for the stated hours/week”

43% said “Too many demands/workload for the stated hours/week”

40% said “Inadequate benefits”

29% said “Lack of funds for professional singers, and/or singers unwilling/unable to commit to regular rehearsals/training”

22% said “Poor facilities or musical instruments”

22% said “Lack of adequate support staff”

28% said “Other”

(Please click on the link below for complete data and stories.)

SURVEY TWO

Of the 288 respondents to the survey “Wounded/Abused Musicians in the Church (USA),” 13% reported never being abused within the Church. One said “I am ignorant of such abuses, and very sorry to know that these things happen,” but sadly that was not the norm.

69% reported having been abused outside of a religious institution, while 87% reported abuse within the Church. 48% claimed abuse by a teacher, mentor, colleague, or classmate. Many of the respondents reported having been abused by more than one person.

Regarding abuse within a religious institution, 82% indicated a member of the clergy, 43% a church leader, 35% a parishioner (member of the congregation), 30% a member of the staff, 24% a volunteer singer/musician, and 20% a non-clergy boss. For abuses outside of religious institutions, 42% reported a family member, 28% a spouse or partner, 27% a friend, colleague, or acquaintance, 13% a teacher or mentor, and 11% a stranger. For abuses within the field of church music (but outside church), 34% indicated a teacher or mentor, 27% an esteemed professional colleague, 27% a professional colleague or friend (at same level), and 12% a classmate.

30% of respondents indicated criminal abuse outside the Church, and 7% said they weren’t sure if the abuse was a crime. 17% indicated criminal abuse within a church or religious institution, and an additional 17% said they weren’t sure if the abuse was a crime. Of those indicating possible criminal abuse outside the Church, 55% reported the crime to authorities, while only 26% reported possible crimes within the Church.

14% reported having been involved in a clergy misconduct case, and of those respondents, 31% said a crime had been committed against them. 15% said they weren’t sure whether the abuse was a crime.

I asked about professional counseling respondents may have received. Of those abused in the Church, 36% reported that they received counseling which was helpful, 32% said they spoke only to family and friends, 11% received counseling but said it was not helpful, 9% reported that they wanted help, but didn’t know where to turn or whom they could trust, and 9% said they chose not to seek counseling.

Perhaps the most troubling statistics came from the question, “Did you ever feel that the abuse you suffered affected your ability or willingness to pursue your calling/vocation?” Of the total 288 respondents, an alarming 51% answered “Tremendously” or “Significantly”, with higher percentages from those indicating abuse by non-clergy bosses (84%), esteemed professional colleagues (78%), colleagues/friends (73%), volunteer singers/musicians (70%), teachers/mentors (68%), and clergy (67%).

A majority of respondents indicated having close friends abused within the field of church music. Regarding abuse within the Church, 26% reported “One or two” friends, 28% said “Several”, and 13% reported “More than I can count.” Regarding abuse by a teacher, mentor, or colleague in church music, 28% indicated “One or two” friends, 18% reported “Several”, and 6% said “More than I can count.”

(Please click on the links below for complete data and stories.)

IN CLOSING

The stories of David — our ancestral church musician — felling the giant Goliath and escaping the abusive and vengeful Saul, inspire those in need of courage. Our modern survivors and heroes in church music likewise give hope for the reform of seminaries, denominations, leaders, clergy, churches, and institutions. John K. Setser devoted his career to safeguarding the profession, imploring pastors and leaders to beware of prioritizing a “vision” ahead of caring for others like family, listening to them, and creating the right conditions for them to grow and flourish. [20]

I have one more story to share, which is the only example I received of a difficult situation turned around:

Initially the new pastor bullied a colleague and me, until a parishioner spoke to the pastor about the hypocrisy of preaching about “beloved community” but not extending that to staff. The pastor took it to heart and the three of us developed a fabulous working relationship.

We need our clergy, teachers, and colleagues to take seriously this task of reformation, and to invite us into respectful and collegial relationships. May this research and work be a catalyst to a new era of health, fruitfulness, and prosperity for all church musicians.

If you have been wounded in any way, please practice self-care after reading this article or the stories. You may feel triggered by them, and need to talk with a counselor, trusted friend, etc. Please know that you are not alone, and that there is help for all who have been abused. May you know of my prayers for your healing.

Diane Meredith Belcher

Ash Wednesday, 2023

For those wishing to contact me and/or send in their own stories, you may

write to me completely confidentially at davidsharpsaulsspear@gmail.com.

Many thanks to the Journal of the Association of Anglican Musicians for publishing this article in their May 2023 issue.

NOTES

1 The Bible, 1 Chronicles 23: 1-5

2 The Bible, Nehemiah 13: 4-13

3 The Bible, Exodus 25-40

4 James R. Doggette, Sr., Should Our Musicians Be Paid?, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vOwlqtkDcwQ (2012.)

5 Bureau of Labor and Statistics, National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates, www.bls.gov/oes/current/naics4_813100.htm (May 2021.)

6 American Guild of Organists, https://www.agohq.org/about-the-ago/history-purpose.

7 The U. S. Religion Census 2020, https://www.usreligioncensus.org/node/1641.

8 Eileen Guenther, Rivals or a Team? Clergy-Musician Relationships in the Twenty-First Century (St. Louis: MorningStar Music Publishers, 2012), Foreword by Paul Westermeyer.

9 Peter J. Gomes, The Good Book: Reading the Bible with Mind and Heart (New York: William Morrow, 1996), 262.

10 Kevin Dutton, The Wisdom of Psychopaths: What Saints, Spies, and Serial Killers Can Teach Us About Success (New York: Scientific American/Farrar, Straus & Giraux, 2012), 162.

11 Kevin Dutton, guest on “Being Human Podcast No. 157, The Wisdom of Psychopaths: The Church as a Business”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q-v3HEwmHUE (2022.)

12 Dutton, The Wisdom of Psychopaths, 10

13 Ibid, 37

14 Valerie Bolden-Barrett, Types of Abuse in the Workplace, https://work.chron.com/types-abuse-workplace-11426.html (updated June 30, 2018).

15 Diocese of New Hampshire, 2023 Compensation Framework, https://www.nhepiscopal.org/clergy-compensation-manual.

16 NBC Survey of Catholic Church Employees, www.nbcmiami.com/investigations/survey-reveals-employees-of-catholic-church-divided-on-clergy-abuse-and-reforms-2/2158454 (2019.)

17 Ibid.

18 Thomas Plante, Psychology Today: Top 10 Myths About Clergy Abuse in the Catholic Church, https://archokc.org/clergy-abuse-myths (2018.)

19 Edwin Friedman, Generation to Generation (New York: Guilford Press, 1985), 53.

20 “Staff Abuse: Can It Happen Here?”, https://research.lifeway.com/2015/10/13/staff-abuse-can-it-happen-here (2015.)

Websites accessed February 2023.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ballou, Hugh. Moving Spirits, Building Lives: The Church Musician as Transformational Leader. Kearney, NE: Morris Publishing, 2005.

Birch, Bruce C. and Parks, Lewis A. Ducking Spears, Dancing Madly: A Biblical Model of Church Leadership. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2004

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Life Together: A Discussion of Christian Fellowship, John W. Doberstein, translator. New York: Harper & Row, 1954.

Day, Katie. Difficult Conversations: Taking Risks, Acting with Integrity. Herndon, VA: Alban Institute, 2001.

De Waal, Esther. Living with Contradiction: Reflections on the Rule of St. Benedict. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1989.

Dimmock, Jonathan. “Fifty Years on the Bench” (in multiple parts), 2022–2023. https://www.jonathandimmock.com/blog. Accessed March 2023.

Dutton, Kevin. The Wisdom of Psychopaths: What Saints, Spies, and Serial Killers Can Teach Us About Success. New York: Scientific American/Farrar, Straus & Giraux, 2012.

Ehrich, Tom. Church Wellness: A Best Practices Guide to Nurturing Healthy Congregations. New York: Church Publishing Incorporated, 2008.

Friedman, Edwin H. Generation to Generation: Family Process in Church and Synagogue. New York: The Guilford Press, 1985.

Gomes, Peter. The Good Book: Reading the Bible with Mind and Heart. New York: William Morrow, 1996.

Greenleaf, Robert K. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness, 25th Anniversary Edition. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2002.

Guenther, Eileen. Rivals or a Team? Clergy-Musician Relationships in the Twenty-First Century. St. Louis: MorningStar Music Publishers, 2012.

Johnson, Spencer. Who Moved My Cheese? An Amazing Way to Deal with Change in Your Work and in Your Life. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1998.

Koch, Ruth N. and Kenneth C. Haugt. Speaking the Truth in Love: How to be an Assertive Christian. St. Louis: Stephen Ministries, 1992.

Lawson, Kevin E. How to Thrive in Associate Staff Ministry. Bethesda, MD: Alban Institute, 2000

Lencioni, Patrick. The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Leadership Fable, 20th Anniversary Edition. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2011.

Long, Thomas G. Beyond the Worship Wars: Building Vital and Faithful Worship. Herndon, VA: Alban Institute, 2001

Maxwell, John C. Teamwork 101: What Every Leader Needs to Know. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2009

Orr, N. Lee. The church music handbook: For pastors and musicians. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1991.

Roberts, William Bradley. Music and Vital Congregations: A Practical Guide for Clergy. New York: Church Publishing Incorporated, 2009

Setser, John K. Broken Hearts, Shattered Trust: Workplace Abuse of Church Staff. [n.p.], 2006.

Sirota, Victoria. Preaching to the Choir: Claiming the Role of Sacred Musician. New York: Church Publishing Incorporated, 2006

Weiser, Conrad W. Healers: Harmed and Harmful. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1994.

Westermeyer, Paul. The Church Musician, Revised Edition. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1997.

For those wishing to contact me and/or send in their own stories, you may

write to me completely confidentially at davidsharpsaulsspear@gmail.com.